Lines of Development

A Discussion on Developmental Lines Through the Great Nest — Integral Theory 101 #2

This is the second edition in a series devoted to illustrating Integral Theory. For the rest of the articles check out them out here: Introduction, Nature of the Self

Introduction

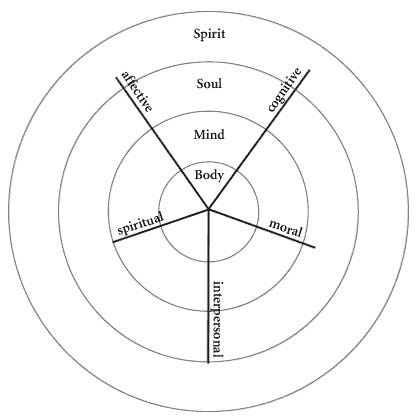

In a previous installment of this series on integral theory, we discussed the Great Nest of Being and the different levels of consciousness development from “dirt to divinity.” We discussed how evolution moves from matter, to body, to mind, to soul, to spirit—the ground of all being. We saw how at each level we transcend and include the level below it—the body exists of matter, yet transcends the quality of matter; the mind exists in the body, yet transcends the function of the body. We can divide the levels any way we want, but with the Great Nest the ancient philosophers hit the nail on the head.

In his book Integral Psychology, Ken Wilber includes pages of graphs illustrating the different traditions from antiquity, all describing in their own way the general Great Chain of Being. Furthermore, these stages described by the perennial philosophers (thinkers from this era), align with empirically based evidence of psychological development.

These graphs illustrate as many different models of development, from spiritual to empirical. It is striking to look at how they all follow a similar pattern, albeit in their own way. These stages are all outlined in the Great Nest and prove why it is a simple yet effective map of development; from matter to spirit.

For further detail on the various systems of development that show this overlapping nature, I highly suggest you read Integral Psychology. There are pages of charts that illustrate how this process occurred in many different societies, with many different thinkers.

Just to reiterate from the previous article, the Great Chain of Being is not a linear development, but rather a nest of development. Each level transcends and includes the former—evolving in a nested manner—with each level encompassing the next. These form different stages or levels of development that we can use to orient our own growth. These levels are not strict guidelines however, but gentle persuasions on the river of expanding consciousness.

Developmental Lines

Now that we have discussed the ground of consciousness development, we can turn our attention to how exactly we move through these levels of being. Life is not so straightforward that we simply progress from one level to the next. It is instead a tangled mess of learning as we blindly feel our way through the challenges thrown at us. Due to the randomness of life’s circumstances we may be well developed in a particular area of life, yet severely lacking in another.

When we look at the various areas of life we can roughly put them into 24 relatively independent categories. Wilber describes them as “morals, affects, self-identity, psychosexuality, cognition, ideas of the good, role taking, socio-emotional capacity, creativity, altruism, several lines that can be called ‘spiritual’ (care, openness, concern, religious faith, meditative stages), joy, communicative competence, modes of space and time, death-seizure, needs, worldviews, logico-mathematical competence, kinesthetic skills, gender identity, and empathy—to name a few of the more prominent developmental lines for which we have some empirical evidence” (Wilber 2000). Of course there are an infinite number of ways we can categorize these developmental lines, but these are the major ones Wilber puts focus on.

Each of these lines are relatively independent from one another—they can develop in their own way at their own pace. Thus, overall development is not linear as previously mentioned. However, when we take each line into account we find that there is a sense of sequential, holarchic development. Each stage must be incorporated and none can be skipped. Each line unfolds in a (mostly) holarchical manner according to the trends of the Great Nest of Being—a “physical/sensorimotor/preconventional stage, a concrete actions/conventional rules stage, and a more abstract, formal, postconventional stage” (Wilber 2000). Or put simply, body, mind, and spirit.

When someone first learns a musical instrument, for instance, they must learn the physical sensorimotor skills, i.e. how to hold the instrument, how to produce sound, etc. As the beginners advance they learn to play songs, grasping the rules of the instrument and then transcending into the abstract by writing music and creating with the instrument. We can go even further into the transpersonal realms and say that at the soul level one learns to use the instrument as an extension of being—an extra limb designed for emotional expression.

The Great Nest of Being is a simplified version of development meant to generalize and encapsulate all the levels. Each line can go through many more than the simplified stages represented in the Great Nest, but will nonetheless line up in some form.

As is extremely important to mention, each line does not develop at the same time. Someone can be very well advanced in their cognitive abilities—possessing a very high IQ—but have a very underdeveloped moral compass. It is easy to fall into the trap of judging someone’s most developed line as the sum total of their development, but this would be false. It is best to look at others and ourselves in a full spectrum of self.

The Self

In psychological theories centered around the inner world and navigating its terrain, the concept of self is important to discern and understand. I have written before on the nature of self which you can read here. In terms of the integral model, the self is the final piece that forms the bones of self-awareness. Together with the levels and lines of development, we have the trifecta of integral theory.

Let us first discuss the nature of self. There are many different iterations of what the self is, including the Jungian model describing a smaller self and larger unifying Self that I have previously written about. For this purpose, we will be discussing a more transpersonal view of the self that helps us navigate the lines and levels of consciousness.

Take a moment to get a good idea of your self as it is right now—simply notice what it is that you call “you.” You may notice that there are two distinct parts to this self: “one, there is some sort of observing self (an inner subject or watcher); and two, there is some sort of observed self (some objective things that you can see or know about yourself—I am a father, mother, doctor, clerk; I weigh so many pounds, have blond hair, etc.)” (Wilber 2000). In short, the first is experienced as an “I,” while the second as a “me” (or even “mine”).

The first can be called the proximate self, and the second the distal self. The first is closer to “you”—literally the observer—while the second is further: definitions of who you think you are, accrued throughout the years. Both of them together form the overall self.

These distinctions are important because “the ‘I’ of one stage becomes the “me” at the next” (Wilber 2000). This means that as you progress to a higher stage of development, what was once identified with at one level tends to become transcended, dis-identified with, or de-embedded at the next. This allows us to see our beliefs and identifications more clearly and objectively, fostering growth. Here we can see the fruit of learning disidentification (re: this article) to aid in this process.

Because this overall self includes all the lines of development rolled into one, it does not develop linearly. Rather it zooms about on the Great Nest, attuning to whatever aspect of life is important for you at that moment. However, the overall self progresses on its own line of development. So while the self does not progress linearly in regards to the different lines of development, it itself develops in a sequential fashion. This means as the self develops alongside the different parts of who you are, it strengthens, and grows in its own manner.

The general process can be shown as follows: The Great Nest of Being does not possess any nature of self—it is simply potentials of human growth. The self simply develops through these potentials, like a raft floating down a great river. It “first identifies with a level and consolidates it; then disidentifies with it (transcends it, de-embeds from it); and then includes and integrates it from the next higher level” (Wilber 2000).

When one transitions to a higher level of awareness it is crucial that the lower levels are included in the overall awareness. For example, the child still remains in the adult although it is no longer the driving force of the personality. It is when we deny the existence of our inner child that it threatens the authority of our inner adult, taking over at inopportune times. We must acknowledge the lower levels as being a part of the higher ones. The key is transcend and include.

Again, because the self has access to all the different types of experiences (through the different states of consciousness as discussed previously) the self can exist at any level, at any time. Just because it has undergone the process above on a certain line does not mean it is rooted there (it will have peak experiences and aim higher, or regress into lower levels of awareness). Overall, the self tends to have a center of gravity—a place on the Great Nest where the self is currently developing at. This is the average of all your specific lines of development and the stage they are at.

When the self transcends a level it experiences it as a mini death. This process can be quite terrifying and is the primordial struggle with the threat of nonbeing discussed in this article. The very life of the self is wrapped up in its identification with that level, and transcending it requires a relinquishing—a decision to face the unknown potential of a transcended level of awareness. This can be terrifying and even traumatic. It nonetheless is an important step to take on the inner journey of raising our level of self-awareness.

This death is only permitted by the self because of the enticement from the higher level. The promise of heaven must outweigh the threat of hell for the self to transcend its current level of awareness—in any line of development. It is this reason that many struggle to escape their own bondage—remaining instead in an apathetic, familiar comfort zone—than face the unknown risk of anything else. Even if it will be infinitely better.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the Great Nest of Being is not a concrete model but rather a series of potentials that we can evolve into. The multitude of selves within us each have their own course of development that moves through these levels. We can assimilate then together to form the overall self—the great navigator of life.

Within this self we can again divide it into different perspectives of experience. We experience our core sense of I-amness, as well as a removed collection of ideas on who we are. In order to grow we must learn to disidentify with and observe objectively our ideas of self, allowing for the potential to transcend into ever deepening levels of awareness.

If you’ve read my other articles on the primal wound you will hopefully by now see the parallels presented between these two theories. Integral theory offers a beautiful road map we can use to place all the different therapeutic modalities within—a toolbox that can sort our tools for when we need them. It is not necessary to rely on one therapeutic technique over another—they all have merit and need in their time—but to instead use what is naturally being highlighted by the self. When we listen to our own deeper, inner wisdom, we will know which area of life we must focus on and will naturally find ways to help us grow. Integral theory simply allows us to see clearer the inner space that is often so clouded in mystery.

— Recommended Reading —

Integral Psychology by Ken Wilber

A Brief History of Everything by Ken Wilber

If you liked this post, subscribe to Archetypical below!

If you know anyone who may like this post, please share it with them:

You can also support my work with a donation: