The Jungian Self

An Introduction to the Psyche’s Transcendent Center of Wholeness—The Jungian Psyche #7

Introduction

Throughout the development of depth and transpersonal psychology, something rather interesting happened. Though there have been quite a few distinct theories on how the psyche is internally structured, in every proposed model there has been an emerging thematic centerpiece—The Self.

This Self is an inner image of wholeness. Through all the highs and lows of consciousness and the unconscious, there seemed to be a single point—an ultimate perspective—that oversees the entirety of what occurs within an individual. To Jung and others in the depth and transpersonal field of psychology, the term Self (distinctly with a capital S) arose to label this aspect of inner wholeness.

This idea was not new in the realm of the inner world. Many different spiritual traditions have some word for this elusive center of wholeness. This inner resource is what the Buddhists label as the Buddha Mind or Buddha Nature. It is also referred to as Atman in Hinduism. In new-age theology, this is the seat of our Christ Consciousness. In a sense, it is the inner experience of transcended wisdom and the goal of all spiritual pursuits. Hopefully we can begin to see how incredibly important it is!

Though Jung wasn’t the first to identify this function of consciousness, he was indeed one of the firsts to write about it in depth in a psychological manner. In fact, the essence of the Self was a critical fulcrum to his entire theory of psyche. One of his most famous texts, Aion, is devoted to describing this ephemeral psychic presence.

In a sense, the Self is who we really, truly are. It is the totality of our personality—the sum of both conscious and unconscious aspects. In itself, it is inherently whole and carries with it values of innate love, compassion, wisdom, and gnosis. It is effectively our inner Imago Dei, i.e. our own inner image of God.

Though the scope of the Self is tremendous, and though we could spend quite a great deal of time discussing the Self throughout different esoteric and spiritual disciplines, let alone psychological models, this article will mainly be focusing on the interpretation of the Self as it fits within the theories of Carl Jung.

Of all the concepts in depth psychology, and particularly that of Jung’s, the Self is perhaps of paramount importance. If anything else, learning to connect with your Self and integrate its perspective is the whole purpose of being conscious—it is the individuation process. Quite a statement, I know. By the end of this article you may begin to see why.

The Self According to Jung

An aspect of the Self that was distinct to Jung was that he regarded it as wholly transcendent. This means that the Self was not, and could not be defined by the bounds of the psyche alone, but existed solely outside and “beyond,” essentially defining it.

This creates an interesting paradox, being that the Self is not technically who one is, at least in part. In his book, Jung’s Map of the Soul, Murray Stein writes:

“It is more than one’s subjectivity, and its essence lies beyond the subjective realm. The self forms the ground for the subject’s commonality with the world, with the structures of Being. In the Self, subject, object, ego and other are joined in a common field of structure and energy” (Stein, pg. 152, 1998).

This gives the Self a distinct non-dual essence. In other words, we can say that the Self is both immanent (existing within) and transcendent (existing beyond) from the experience of who one is. This paradoxical nature is what makes the Self so difficult to grasp, yet it is also the key to fully understanding and integrating the Self within the totality of who you are.

Because the Self is the seat of wholeness, it is truly unique to who you are. Our ploys at being original within the confines of the ego pale in comparison to the true originality that your Self has to offer. Not only is the Self unique to each individual, but the path that one takes to discover and integrate the Self is equally unique.

By itself, the Self is operating on the same basic principles in each person (and animal.. and plant and thing if you want to take it that far). It is the basic premise of I-am. The divine spark of consciousness that animates each living thing. Fundamentally, we are all experiencing the same essence of first-person perspective. This is our core I-amness that everyone has.

The path towards discovering the extent of what this means for us is where our individuation journey lies. For Jung, his discovery of his Self came with the understanding that at the bottom of the psyche there rests a fundamental structure that can never be broken, no matter how severe the threats of abandonment and betrayal may be.

This is the nature of our Self. It is perfectly whole, perfectly healed. It has the capacity to impart eternal wisdom and behave as an inner mentor, therapist, parent, friend, lover, and God. It is eternal and indestructible. It is an infinite wellspring of vitality, hope, and love.

The Self behaves like a north star to the ego. It is the light in the center of the storm that ceaselessly guides the ego towards its ultimate goal of wholeness.

The best part is we each have this within us, and can learn to tap into, integrate, and fully embody this beautiful presence.

Definitions

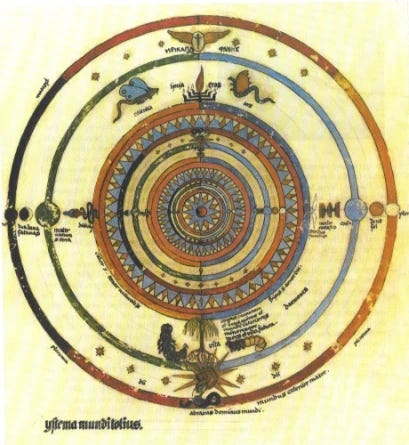

At its core, the Self is a symbol of order. Jung first observed this inner structure coming to light within him when he was driven to spontaneously start drawing mandalas. A mandala is an image of a circle containing some type of geometric structure within it. To Buddhist monks, it represented the order of the cosmos itself. To Jung, this image correlated strongly with the observations of the Self he was having.

The Self is, as stated before, the center of wholeness. When the Self is integrated and realized consciously, we feel this wholeness subjectively. Technically, it is impossible to fully realize. The Self is always generating new material to integrate, but throughout the process of individuation, we can make considerable progress.

Jung also believed that it was impossible to come into this union of wholeness without first dealing with the issue of the Anima and Animus. The Anima/us are the basic duality or polarity within the psyche. Integrating this basic duality (known as the syzygy) is a necessary prerequisite to experiencing the non-dual nature of the Self.

As previously stated, our Self is synonymous with the image of God. It is the “God-spark” of consciousness present within all of us. It is, in a sense, the original archetype. Maybe the “arche-archetype.” In a way, we can see the Self as the archetype of who we are as an individual. If the ego bears the marks of the personality as it is currently manifested, the Self contains the unmanifest information of you as a form of pure potential. This is what makes it archetypal in nature.

When people spontaneously begin producing symbols of the Self, such as the mandala, in dreams or drawings, it suggests that there is a strong need in the psyche to be integrated. This image comes through when the Self is not present, obscured, as it were, like clouds over the sun.

This is usually right before the psyche is on the verge of fragmenting. Right in our darkest moments is when the Self emerges as the guiding light, our own inner image of hope and love that descends like a guardian angel and guides our forlorn soul home.

Any symbol that bears the image of wholeness and unity is likely coming from the Self. Its sole purpose is to oversee the psyche and bring harmony to all its various parts. This unity has a dynamic nature to it, made manifest through becoming increasingly balanced, interrelated, and integrated.

In a way, we can see the Self as operating over the entirety of our conscious and unconscious experience in the same way the ego operates over our personal field of consciousness. Whatever is within the scope of our ego, we feel a need to bring order to it in some form. We feel responsible, or in other words, identified with it.

In a similar way, the Self is responsible for our conscious and unconscious material, and bringing order and unity to it. In a hierarchical sense, all the various components we have discussed in previous installments (such as complexes, the shadow, the persona, the Anima/us) are all under jurisdiction of the Self. They all have their own autonomous agenda, and the Self is solely interested in getting them to work together.

Finally, Jung believed that there was a direct and privileged relationship between the ego and the Self. This he quite fittingly called the ego-Self axis. Because of this relationship, it could be argued that the Self is actually more of a super-egoic attribute of the ego. To Jung, however, the Self was strictly transpersonal in origin. It existed beyond the psyche, and as mentioned, had a transcendent-immanent quality to it. When it comes to the Self, we are not dealing merely with an egoic projection. We are dealing with something truly divine.

Symbols of the Self

In Aion, Jung’s preeminent text on the phenomenology of the Self, Jung discusses various symbols that have arisen throughout Western history that are possible depictions of the Self. He is mostly concerned with those prevalent in alchemy, Gnosticism, and astrology.

Of those noted, Jung writes about geometrical structures, (such as the mandala circle discussed earlier, as well as the square and star). These may appear in dreams or consciousness without any special attention given to them (such as an ordinary, four-legged table).

Following this, the number four (and multiples of four) are incredibly important and deeply symbolic of the Self. In addition, precious gems, royal figures, or even animals such as the elephant, horse, bull, bear, fish, or the snake can represent the Self.

The Self can also be represented by organic or inorganic images such as those found in nature. In addition, Jung wrote about how the Self can be represented as a phallus. This is particularly the case when sexuality is undervalued, either through repression or in overt devaluation.

Really, the Self can appear as any symbol. Like all symbols, what matters most is the individual's relationship to that symbol. The ones listed above are averages, and you may very well experience one of these as an image of the Self trying to come through. Each individual is unique, however, and you’ll know that it is the Self you are dealing with because of the energy of wholeness that accompanies the image.

As noted, the Self has a paradoxical nature to it. Whatever the symbol that appears for you, it will carry the essence of being both/and. It is male and female, old man and child, powerful and helpless, large and small, good and evil. Overall what matters is how you show up to experience the Self. When you change, so will the images that bear the Self energy.

Diagrams

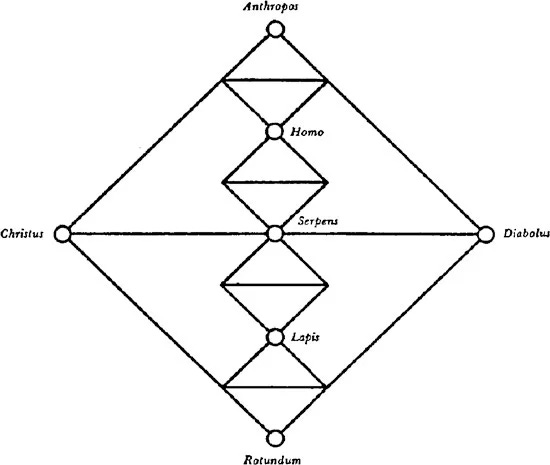

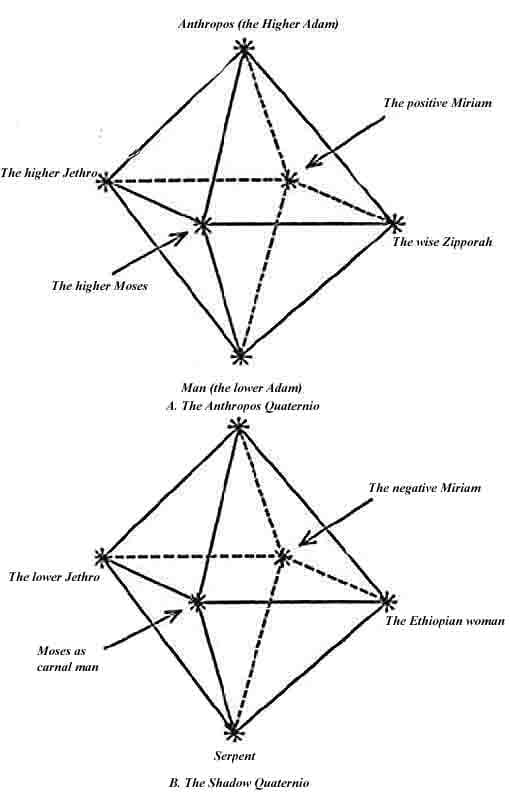

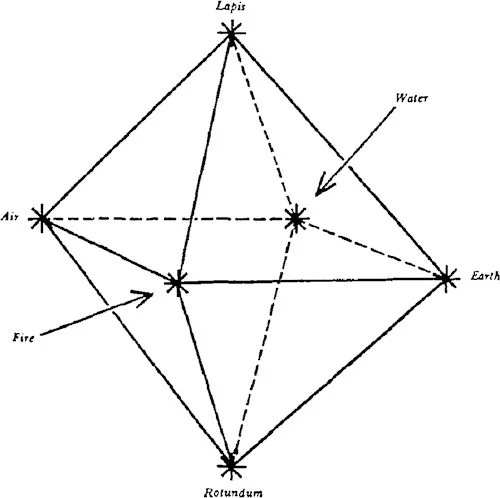

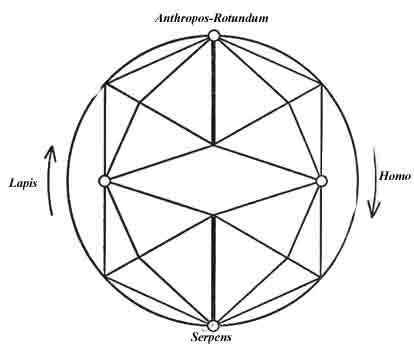

Throughout his research into the Self, Jung produced a series of diagrams that attempted to depict the structure of the psyche he was observing.

Fundamental to his diagrams, and following the symbolism of the number four being analogous to the Self, Jung depicted a series of quaternities—pyramidal shapes that can be placed together in the form of a three-dimensional, six-pointed figure. These were important if we recall that the number four is quintessential in describing the Self.

These diagrams depict a series of levels that extend both below and above ego consciousness (located at the Homo level). With this we can see where we exist as ego-conscious beings. Above this level is the level of potentials and ideals, labeled Anthropos. This is where the Self is located.

Below the Christus—Diabolus line exists the shadow of the two quaternities already discussed. Here, a direct reflection of the positive ideal found in the Self and Anthropos is located. Jung was keen on describing the nature of the anti-Self. If the Self was a symbol of wholeness and goodness, the Anti-Self was the shadow form of evil and fragmentation. We can’t have light without darkness.

While Jung decided to limit the scope of his theory by establishing a loose boundary at the end of the collective unconscious, he was still open to the idea that consciousness could descend down through the animal, vegetative, and even mineral and subatomic levels of reality. Following certain trends in panpsychism, as well as spiritually intuitive people who are able to become conscious of these layers, this could certainly be the case.

If anything, the two shadow quaternities, which house the inorganic and deep unconscious levels of the psyche, can support the many myths of “descending into the underworld,” to reclaim lost, vital aspects of oneself. This descent into the underworld may be symbolic of the “unconscious,” as much as it may have a direct correlation to descending to the level of consciousness that inorganic substance experiences.

Much like Dante’s famous journey through hell, at some point you reach the bottom, move through the beast and begin to ascend again. In this sense, Jung drew a diagram of this cyclical nature of the quaternities, revealing how they were connected.

Movement through consciousness, from deep unconscious to hyper-conscious is, like most things in life, cyclical in nature. Moving through the unconscious, the underworld, we can rise again to ever higher states of consciousness, eternally reclaiming more and more elements of the Self and our potential for wholeness.

The Central Mystery of the Psyche

By now you will have a clear understanding of how Jung viewed this beautifully elusive psychological factor. Hopefully you will see its importance, and why moving towards a state of wholeness is, as Jung put it, our task imposed on us by nature. To make the unconscious conscious is to impart order on the chaos. To find the essence of who we really are and incarnate as that being.

Before concluding this article, I would like to briefly discuss my own experiences of the Self. Perhaps the biggest flaw and critique of Jungian psychology is that it is too analytical. It is too intellectual. Personally, I can see how the psychology itself has become very cerebral and analytical. Reading Jung’s writings and about his experiences, I don’t believe it was purely analytical for Jung. He was very much deeply entrenched in the experience of the psyche, which led him to so passionately document what he had found.

This is where the crucial part to understand is. The Self, and really any archetype (but most importantly the Self), is not something to be abstractly understood. You can study the symbols, but it will be meaningless unless you have the experience of it. In Aion, a text I have mentioned many times in this write-up, Jung heavily stressed the importance of the subjective, feeling-tone of the psyche. He states how psychology had lost touch with this aspect, and was missing out, if not making a dramatic error, in truly understanding the psychological experience (I wrote more about his topic here).

Ultimately you know the Self not by the symbol, but by the way it feels. It would be fair to say that the Self is synonymous with life-force, with vitality. There is a mystical pulsation to the Self that thrums in the heart and swells in the soul. An all pervasive sense of being alive, and being very content with being who you are is profoundly present. It is not just witnessing the north star, but being the north star. A deep knowing overcomes you, a true gnosis.

It wouldn’t be that far-fetched to say that the Self is really just psychological jargon for referring to something that most of us have an intuitive understanding of already—the soul.

When we are living from this beautiful source, this god-image within, it is nearly impossible not to radiate peace, bliss, hope, and harmony. No longer do we have to hope that the weather won’t obscure the sun. When we embody the Self, we become the sun.

Previous Installments of the Jungian Psyche:

If you liked this post, subscribe to Archetypical below!

If you know anyone who may like this post, please share it with them:

You can also support my work with a donation:

I exist in all things. 👁